The retro kitchen that changed how the desert lived

Lost Palm Springs: The Retro Kitchen Where a Martini Met a Mixing Bowl

In the Lost Palm Springs series, we usually chase what’s vanished—demolished restaurants, renamed motels, and architectural nightclubs remembered mostly through rumor and grainy photos. But occasionally what’s truly “lost” isn’t a place at all. Sometimes it’s an idea.

There’s a particular kind of magic to a Palm Springs kitchen from the late ’50s/early ’60s: it’s not trying to be the star of the show… and that's exactly why it is. Like a good party host, it’s stylish without being showy, practical without feeling utilitarian, and always keeping one eye on the conversation—and the cocktail tray.

Nowhere does that vibe hit harder than in the Alexander Construction Company homes designed by William Krisel (Palmer & Krisel) in Racquet Club Estates—a neighborhood built at scale but with a surprisingly thoughtful sense of variety and livability. Dwell notes the tract was developed roughly 1959–1962, with plans “tweaked…to create a non-repetitive tract,” plus multiple roofline options and exterior details to keep the streetscape from feeling copy-paste. Dwell Magazine

Few spaces capture that better than the original mid-century kitchens found in Racquet Club Estates, developed by Alexander Construction Company and designed by William Krisel of Palmer & Krisel. These kitchens weren’t meant to impress with size or luxury. They were designed to work—quietly, efficiently, and always in service of desert living.

There’s a particular kind of magic to a Palm Springs kitchen from the late 1950s and early ’60s: it doesn’t try to be the star of the show… and that's exactly why it is.

The bigger idea: a kitchen that matched a new kind of life

The real story of retro kitchens in Palm Springs isn’t just about cabinet doors and tile (though, yes, we can happily spiral into that). It’s about a cultural shift: modern homes were designed around informality—cocktails, patios, casual dinners, kids running in and out, and neighbors dropping by. The kitchen stopped being a hidden utility room and became a command center for desert living.

And if you want the perfect summary of a Krisel/Alexander kitchen in Racquet Club Estates, it might be this:

It wasn’t built to impress your grandmother.

It was built to keep your guests close—and your martini closer.

A Space-Age Kitchen, Desert Edition

Krisel’s kitchens echoed the same architectural philosophy as the homes themselves: post-and-beam construction, clerestory windows, open planning, and a seamless indoor-outdoor relationship that made the whole house feel like it breathed with the pool and patio.

One of the most talked-about details—and a favorite among mid-century purists today—was the cabinetry. Racquet Club Estates kitchens often featured what have been described as “space-age” cabinets, a term that sounds playful but is surprisingly accurate. These weren’t traditional, heavy millwork cabinets meant to blend into the walls. They were graphic, lightweight, and intentionally modern—cabinetry that looked more like furniture than built-ins.

Pegboard Cabinets: Design Innovation or Cost-Cutting?

Which brings us to the detail that still sparks debate: pegboard cabinet doors.

Yes—pegboard.

Source: Paul Kaplan Group photo archive

At first glance, it feels almost shocking by today’s standards. But the question is worth asking: Why pegboard? Was it purely about cost, or was design the real driver?

The Alexanders were famously disciplined about expenses. Their entire mission was to deliver modern architecture to the middle class, and that meant watching every dollar. Pegboard was inexpensive, lightweight, easy to install, and readily available. From a builder’s perspective, it made sense.

But to dismiss pegboard as “cheap” misses the bigger picture. Pegboard also fit squarely within mid-century modern ideals. It was industrial. It was honest about its material. It introduced texture and rhythm. And it allowed for airflow—an underrated benefit in the desert before modern air conditioning was widespread.

Photo credit: Alexander Construction Company kitchen, Racquet Club Estates, Palm Springs, c. 1959–1961.

Photograph by Julius Shulman.

Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

As for precedent: pegboard cabinetry was not common in mainstream residential kitchens at the time. That’s what makes its use here notable. It wasn’t copied from tradition—it was adapted. In that sense, it feels very much like a Krisel move: pragmatic, experimental, and visually forward-looking.

The likely truth? It was both. A cost-effective solution that also aligned perfectly with the modernist aesthetic.

Boomerang Legs, Floating Cabinets, and a Kitchen That Moved

Supporting those base cabinets were wire boomerang legs, another instantly recognizable feature. These slender metal supports lifted the cabinetry off the floor, making the kitchen feel lighter and more open—less like a utility room and more like an extension of the living space.

Photo credit: Alexander Construction Company kitchen, Racquet Club Estates, Palm Springs, c. 1959–1961.

Photograph by Julius Shulman.

Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute.

And then there was the movable island. It was not a massive, immovable slab of stone, but a flexible, mobile work surface that you could reposition as needed. Cooking for two? Slide it aside. Hosting friends? Roll it closer. It was a kitchen designed to adapt to the moment, not dominate it. (However, once the cabinets were filled with dishes, it was a pretty heavy piece so I don't know how often people would actually move it!)

Before “Open Concept” Became a Buzzword

Today’s open kitchens feel inevitable. In the late 1950s, they were quietly revolutionary.

Traditionally, kitchens were hidden—functional spaces tucked away from guests. Krisel’s Racquet Club kitchens challenged that norm. Through open sightlines and pass-through openings, they allowed the cook to stay connected to the living and dining areas. The kitchen didn’t disappear; it participated.

In Palm Springs, this mattered. Desert living has always been informal—poolside cocktails, neighbors dropping by, dinners that drift outdoors as the sun sets behind the mountains. These kitchens became command centers, not back-of-house spaces.

Formica: The Material That Made Modern Living Possible

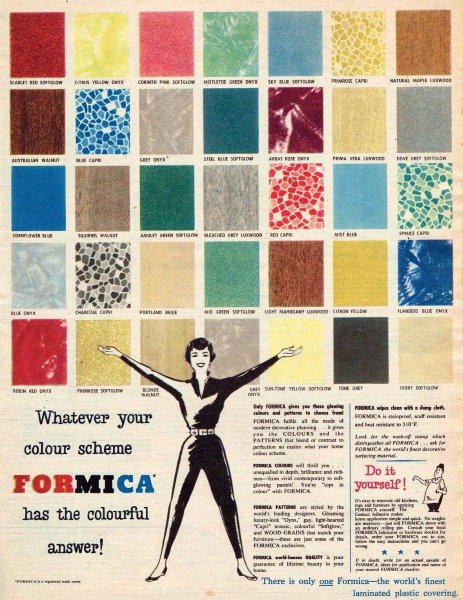

No discussion of Palm Springs retro kitchens is complete without Formica.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Formica wasn’t a compromise—it was the future. Durable, heat-resistant, easy to clean, and available in an explosion of colors and patterns, it is perfectly suited to desert life. You’d find it on countertops, cabinet faces, backsplashes, and tables—often finished with metal edging for a crisp, graphic look.

Formica handled wet swimsuits, spilled cocktails, sandy feet, and buffet-style entertaining without complaint. More importantly, it aligned philosophically with the Alexander homes themselves: modern design for everyday people, not just the elite.

One reason Formica fit so seamlessly into mid-century modern kitchens is that it didn’t try to be anything else. Unlike today’s engineered surfaces that aim to mimic marble or stone, Formica was proudly modern—flat, graphic, and unapologetically synthetic. That honesty aligned perfectly with mid-century modernism’s core values: materials should express what they are, not disguise themselves as something more “luxurious.”

Invented in the early 20th century as an industrial laminate and popularized after World War II, Formica evolved into a residential staple just as America embraced optimism, efficiency, and forward-looking design. Its durability, ease of maintenance, and bold colors made it ideal for Palm Springs living, but its real success came from philosophy: Formica didn’t imitate the past—it represented the future, and in mid-century modern homes, that confidence was the point.

Built for the Many, Not Just the Few

Alexander Construction wasn’t creating custom showpieces for movie stars alone. They were building for teachers, salespeople, retirees, and snowbirds—hundreds of homes at a time. Efficiency mattered. Materials mattered. Design had to be repeatable without feeling cheap.

The result was a kitchen that looked to the future while staying grounded in practicality—exactly what mid-century Palm Springs did best.

The retro-kitchen details people fall in love with (and recreate)

When people renovate these homes today, they often try to recapture that original “future-from-1960” feeling rather than bulldoze it. One Atomic Ranch tour describes a renovation team using old photos of Krisel’s Racquet Club Estates houses to rebuild a kitchen close to the originals—and even referencing plans held at the Getty as part of the process. Atomic Ranch

And in restored examples, you’ll often see period-friendly material choices show up again—Boutique Homes highlights an eat-in kitchen in a restored Racquet Club Alexander with Heath tile and terrazzo countertops, paired with walls of glass looking out to the pool. Boutique Homes

That combo nails the Palm Springs formula: practical surfaces, cheerful texture, and a constant visual connection to outdoors.

Kitchens in Practice: Past & Present

One of the most famous real-world snapshots of this Palm Springs kitchen ethos appears in a Life Magazine photo shoot from the early 1960s featuring Steve McQueen at his Palm Springs home.

Life Magazine, early 1960s — Steve McQueen at his Palm Springs home.

© Life Magazine / Getty Images

The images—casual, sun-washed, and almost deceptively simple—show McQueen moving easily through a modern house where the kitchen reads less like a “room” and more like part of daily life. There’s no theatrical staging, no showpiece cabinetry competing for attention. Instead, the kitchen feels integrated, efficient, and quietly stylish—the kind of space where someone could fix a drink, grab a snack, or lean against the counter between swims in the pool.

That Life spread helped cement the idea that Palm Springs modernism wasn’t about formality or luxury for luxury’s sake; it was about living well without fuss. In many ways, those photographs captured exactly what the Alexander/Krisel kitchens were designed to do: fade gracefully into the background while enabling a relaxed, modern desert lifestyle that felt effortlessly cool.

Life Magazine, early 1960s — Steve McQueen at his Palm Springs home.

© Life Magazine / Getty Images

Dani Nagel’s reimagined Krisel kitchen beautifully channels the spirit of the Alexander/Krisel kitchen, even though it is not located in Racquet Club Estates. While the original kitchens of the era typically leaned toward more muted, restrained color palettes—soft neutrals, pale laminates, and understated finishes—Nagel unapologetically embraces the color optimism that defined the period.

Source: Atomic Ranch — Dani Nagel’s reimagined William Krisel kitchen, Palm Springs.

© Dani Nagel.

Her kitchen embodies the playful side of mid-century modernism, featuring bold hues, confident contrasts, and materials that feel both period-correct and joyfully amplified. Importantly, the appeal remains the same. The kitchen still reads as open, social, and integrated into daily life rather than a standalone showpiece. Nagel’s reinterpretation doesn’t rewrite history—it highlights it, reminding us that the era wasn’t just about clean lines and restraint but also about experimentation, personality, and a belief that modern living should be fun. In this sense, her kitchen demonstrates that the Krisel philosophy remains dynamic, relevant, and alive in Palm Springs even today.

Source: Paul Kaplan Group photo archive

Source: Paul Kaplan Group photo archive

Source: Paul Kaplan Group photo archive

Source: Paul Kaplan Group photo archive - Starr Road Kitchen Remodel by Paul Kaplan

Why These Kitchens Matter Now

Today, many original Racquet Club kitchens have been remodeled beyond recognition. Pegboard cabinets removed. Wire legs scrapped. Movable islands were replaced with oversized, immovable ones. And while updates are sometimes necessary, something subtle is often lost in the process: the idea that modern living didn’t require excess—it required thought.

That's why these kitchens are a perfect fit for Lost Palm Springs. Not because the houses are gone, but because the design thinking is quietly disappearing.

The original Racquet Club kitchen wasn’t built to impress your grandmother.

It was built to free the host.

And maybe—just maybe—to make sure no one missed the next round of martinis. 🍸

Lost Palm Springs is an ongoing series from The Paul Kaplan Group, dedicated to exploring the buildings, places, and everyday spaces that once shaped life in the desert—and the stories they continue to tell. Through architecture, art, photography, and personal memory, we document what has been lost, what survives in fragments, and what still quietly influences Palm Springs today.

Some of the history shared here comes from archival research, while other details are drawn from oral histories and lived experience. As with any evolving historical record, there may be omissions or inaccuracies. We welcome reader contributions, photographs, firsthand recollections, and corrections, and we view these posts as living documents—updated as new information comes to light.

We firmly believe that understanding Palm Springs' past, not just the architecture but the lifestyle too, helps us better appreciate what remains and recognize what is worth protecting for the future.

Selling Your Home?

Get your home's value - our custom reports include accurate and up to date information.