Desert Inn Fashion Plaza & The Alexanders

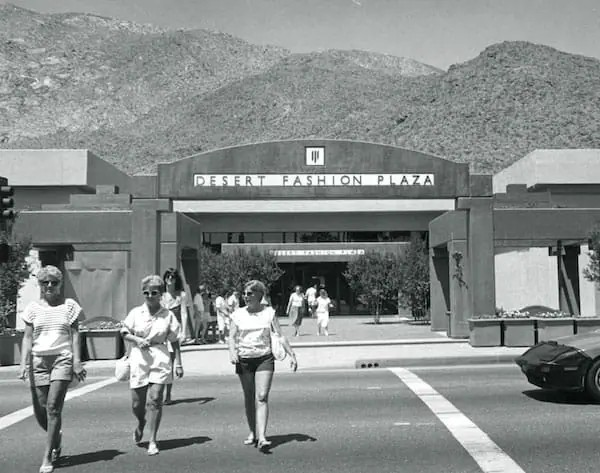

Bell tower entrance at the Desert Inn Fashion Plaza, Palm Springs, c. 1967–1970. Photo courtesy of the Palm Springs Historical Society.

Lost Palm Springs: Desert Fashion Plaza

The mall that replaced a legend, ruled downtown, then waited years to be forgiven

There was a time when downtown Palm Springs had a single gravitational force—and it wasn’t a cocktail bar or a pool party.

It was a mall.

The Desert Inn Fashion Plaza (later renamed Desert Fashion Plaza) was once the shopping and social center of Palm Springs, a place where locals gathered, tourists cooled off, and fashion quite literally came to the desert.

But its story begins with a bold—and controversial—act.

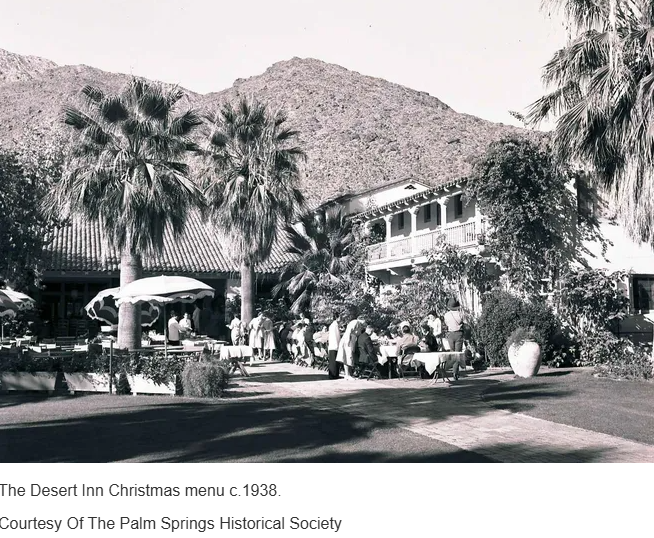

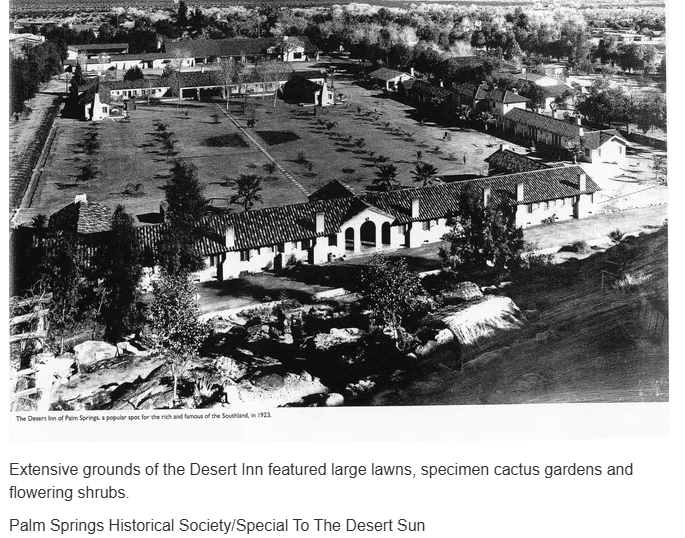

Before the Mall: The Desert Inn and the Alexanders

Long before it became the Desert Inn Fashion Plaza, the site was home to one of Palm Springs’ most important early resorts: the Desert Inn, founded and operated by pioneer hotelier Nellie Coffman. The Desert Inn wasn’t just a hotel—it was the social and civic heart of early Palm Springs, hosting celebrities, politicians, and seasonal residents who helped define the town’s identity..png)

.png)

After Nellie Coffman’s death in the 1950s, her sons sold the property in 1955 to actress Marion Davies, who immediately envisioned a bold new future for the site. Plans were announced for a $4.5 million, five-story hotel and shopping center, complete with a swimming pool, theater, Las Vegas–style restaurant, and parking for 1,000 cars. The project was to be designed by Victor Gruen and Associates, the same firm shaping America’s early mall culture. But Davies’s declining health stalled the project, and it was never built.

In 1960, Davies sold the land for $2.5 million to developers Samuel Firks and George Alexander—a pivotal moment in Palm Springs history.

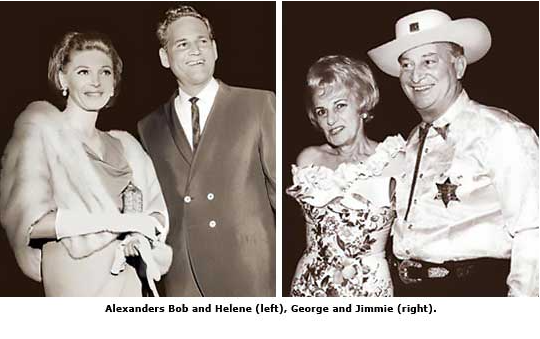

The Alexander Construction Company Moment That Never Happened

George Alexander was not just another developer. He was the driving force behind the Alexander Construction Company, the firm responsible for many of Palm Springs’ most iconic mid-century neighborhoods, like Twin Palms and Racquet Club Estates. The Alexander name is inseparable from the city’s architectural identity.

Alexander and Firks initially planned an eight-story, 300-room hotel with a massive 1,600-car parking facility to replace the historic Desert Inn. But those plans stalled, and attention shifted toward commercial redevelopment instead of hospitality—an early signal that downtown Palm Springs might be headed in a new direction.

Then tragedy intervened.

On November 14, 1965, George Alexander, his wife Mildred, their son Robert, and daughter-in-law Helene were all killed in a plane crash shortly after takeoff from Palm Springs International Airport. The family was killed when their chartered plane flying from Palm Springs to Burbank crashed into the Little Chocolate Mountains near Indio, California. With the Alexander’s sudden death, all redevelopment plans for the Desert Inn site were abandoned.

It’s one of Palm Springs’ outstanding what-ifs: had Alexander lived, the site might have become a hotel or mixed-use development shaped by the same design sensibility that gave us Twin Palms and Racquet Club Estates—rather than a mall.

Were there drawings of the Alexanders’ original plan?

As of now, no known architectural drawings or renderings of the Alexanders’ proposed hotel have surfaced publicly.

The plans are referenced in historical records and news coverage, but no confirmed drawings are held in widely accessible archives such as the Palm Springs Historical Society, local museums, or published Alexander Construction Company collections. It’s possible sketches once existed privately—or were lost after Alexander’s death—but none are currently documented or digitized.

Which somehow makes the question linger even longer.

What if the Alexanders had lived?

It’s one of Palm Springs’ great unanswered questions.

Had George Alexander lived, it’s entirely plausible this site would have become a modernist hotel or mixed-use resort, shaped by the same architectural thinking that gave us Twin Palms and Racquet Club Estates—buildings that engage the street, embrace indoor-outdoor living, and feel unmistakably Palm Springs.

Instead, the land was acquired by Home Savings and Loan in 1966, the Desert Inn was demolished, and the city’s most historic site became an enclosed shopping mall—an architectural and cultural pivot that would shape downtown for decades.

History didn’t choose wrong.

But it definitely chose different.

Why the Alexander connection matters

The Desert Fashion Plaza didn’t rise on neutral ground. It replaced a legendary hotel, was shaped by unrealized Alexander Construction Company plans, and emerged only after tragedy changed the city’s development trajectory. In that sense, the mall wasn’t just a retail experiment—it was the physical marker of Palm Springs pivoting away from its early resort identity and into the modern commercial age.

.png?w=851)

From Desert Inn to Desert Fashion

In the mid-1960s, Home Savings and Loan Association acquired and razed the historic Desert Inn, the legendary hotel founded by Nellie Coffman that had hosted Hollywood royalty, presidents, and generations of sun-seekers.

In 1966, the property was acquired by Home Savings and Loan Association, which moved decisively. That same year, developer Joseph K. Eichenbaum announced plans for a multi-million-dollar commercial center, and architect Charles Luckman—known for bold, corporate modernism—was commissioned to design the project.

After the tragic death of George Alexander and the collapse of earlier hotel plans, Eichenbaum emerged as the figure willing to move the project forward—this time not as a resort, but as a commercial shopping center, very much in step with national development trends of the 1960s.

Eichenbaum’s role was less about architectural vision and more about execution: assembling financing, coordinating with institutional owners like Home Savings and Loan Association, and delivering a project that reflected the era’s faith in enclosed, destination retail. His work represents Palm Springs’ pivot from pioneer resort town to modern consumer city—ambitious, optimistic, and ultimately controversial in hindsight

Charles Luckman was not a local architect—he was a national figure, and his involvement signaled that the Fashion Plaza was meant to be taken seriously. Before architecture, Luckman had been a business executive (famously the president of Lever Brothers), and that corporate sensibility carried into his designs: bold, efficient, and monumental.

By the time he designed the Desert Inn Fashion Plaza, Luckman had already shaped some of America’s most recognizable mid-century commercial buildings, including Madison Square Garden, the Los Angeles Forum, and major corporate headquarters. His architecture favored scale, spectacle, and control, making him a natural fit for large shopping malls.

At the Fashion Plaza, Luckman applied the dominant retail philosophy of the era: shopping turned inward. Climate-controlled corridors, dramatic interior features like fountains and bells, and minimal street engagement reflected the belief that malls should be self-contained environments, offering comfort, consistency, and visual drama regardless of what was happening outside.

Demolition of the Desert Inn began in August 1966, marking the definitive end of Palm Springs’ original resort era on that site.

In its place rose something radically different: a modern enclosed shopping mall, the Desert Inn Fashion Plaza.

The Desert Inn Fashion Plaza officially opened on October 16, 1967, anchored by a 20,000-square-foot I. Magnin—a symbolic return of the retailer to Palm Springs after its earlier presence at the El Mirador Hotel in the 1930s and ’40s. The all-electric design of the mall even earned honors from Southern California Edison, reinforcing its image as futuristic and forward-looking.

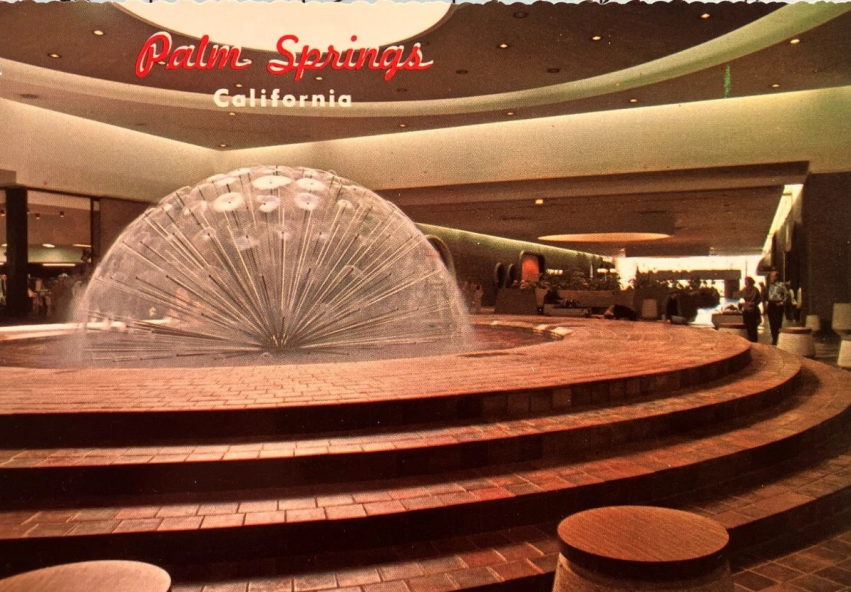

Architecturally, it leaned hard into mid-century spectacle:

A dramatic stainless-steel fountain with nearly 200 polished arms shooting water skyward

A bell tower entrance meant to announce arrival and importance

Wide interior corridors designed for lingering, not rushing

At the main entrance of the Desert Fashion Plaza, visitors were greeted not by glass doors alone, but by bells—a deliberate, almost theatrical gesture meant to announce arrival and importance. The bell feature was part of the original architectural composition designed by Charles Luckman, the mall’s architect, and functioned as a kind of symbolic gateway between Palm Canyon Drive and the interior world of the plaza. While no single artist or fabricator of the bells has been definitively credited in surviving records, they reflected a mid-century impulse to borrow historic civic motifs—church bells, town squares, European promenades—and reinterpret them in a modern commercial context. In a place that had just erased its most storied hotel, the bells offered a sense of continuity and ceremony: this is where downtown happens now. Like the fountain inside, they were meant to slow people down, mark time, and turn shopping into an experience. Long after the stores closed, locals still remembered “the bells at the entrance,” proof that even small architectural flourishes can outlast the buildings they once belonged to.  Desert Inn Fashion Plaza bell tower, c. late 1960s–early 1970s. Photograph courtesy of the Palm Springs Historical Society.

Desert Inn Fashion Plaza bell tower, c. late 1960s–early 1970s. Photograph courtesy of the Palm Springs Historical Society.

When it opened in 1967, it was seen not as a loss, but as progress.

Architecturally, the Desert Inn Fashion Plaza was a textbook expression of its era: bold, confident, and resolutely inward-looking. The mall embraced the postwar belief that the future of shopping belonged inside—controlled, climate-perfect, and insulated from the unpredictability of weather, traffic, and street life. Like many American malls of the 1960s, it turned its storefronts away from the sidewalk and toward long interior corridors, where fountains, art, and polished surfaces created a self-contained world. Air-conditioning wasn’t just a comfort feature in Palm Springs—it was a selling point, allowing shoppers to glide from boutique to boutique in a carefully curated environment, untouched by heat or dust. The problem, revealed only later, was that this design philosophy quietly severed downtown from its streets, replacing organic wandering with programmed circulation. What felt futuristic in 1967 ultimately proved out of step with a city whose greatest asset had always been life outdoors.

The Fountain: Desert Modern

(a centerpiece you could hear before you saw)

At the heart of the Desert Fashion Plaza—on the historic site of the Desert Inn—was a fountain that perfectly captured mid-century Palm Springs’ love of spectacle.

The vintage fountain was a signature modernist landmark, instantly recognizable for its array of stainless-steel arms (or pipes) projecting water in a broad, synchronized display. It wasn’t subtle. It was kinetic, reflective, and unapologetically futuristic—exactly what a 1960s resort town wanted shoppers to feel the moment they stepped inside.

Anchoring the scene was the celebrated Rainmaker sculpture: a 35-foot-tall stainless-steel installation with colorful arms that bobbed and spilled water, adding motion, sound, and drama to the mall’s interior. Together, the fountain and Rainmaker functioned as public art as much as architecture—widely regarded as a standout example of Desert Modern design and one of the Coachella Valley’s most memorable civic artworks of the era.

Importantly, the fountain was conceived for the original, climate-controlled interior of the mall in the late 1960s and 1970s. It was meant to cool the eye, calm the nerves, and signal arrival—you’re somewhere special now. Later renovations that opened portions of the plaza to the outdoors diminished that effect, but for a generation, the fountain was the Fashion Plaza’s emotional center.

Long after the stores faded and the corridors emptied, people still remembered the sound of water echoing off terrazzo and steel—a reminder that, for a time, Palm Springs believed even shopping deserved a little theater.

The Mall Had a Good Run

By the late 1960s and 1970s, the site had fully transformed—from desert resort to modern retail center—reflecting both Palm Springs’ ambitions and the national belief that malls were the future of downtowns.

The place everyone went

At its peak, shoppers truly flocked to the Fashion Plaza. It wasn’t just retail—it was a gathering place, an air-conditioned living room for a desert city. Luxury names like I. Magnin and Saks Fifth Avenue gave Palm Springs retail credibility, while banks, boutiques, and restaurants filled in the rest.

For a generation, this was downtown Palm Springs!

Reinvention in the 1980s: too late, too inward

By the 1980s, however, competition was creeping east.

Palm Desert was growing rapidly, and both the Town Center mall and the increasingly sophisticated El Paseo were pulling shoppers away. Parking was easier. Residents were closer. Retail followed rooftops.

In response, a new owner attempted a major rescue:

The mall was renovated and expanded

“Desert Inn” was dropped from the name, becoming Desert Fashion Plaza

A six-story hotel with underground parking was added

On paper, it sounded like a comeback.

In actuality, it exacerbated the mall's primary weakness: it continued to face inward, abandoning the street at a time when Palm Springs was starting to appreciate the importance of outdoor, walkable urban living.

Saks leaves—and the lights go out.

Desert Inn Fashion Plaza bell tower, c. late 1960s–early 1970s. Photograph courtesy of the Palm Springs Historical Society.

For years, one elegant holdout remained: Saks Fifth Avenue.

Saks became the last major retailer anchoring the Fashion Plaza, long after other stores had left and foot traffic had thinned. Shoppers walked through quiet corridors past empty storefronts just to reach Saks—a surreal experience that perfectly summed up the mall’s decline.

When Saks relocated to El Paseo in 2001, the spell was broken.

Without Saks, the mall was finished.

The long vacancy: a downtown scar

Desert Fashion Plaza exterior after 1980s renovation. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

What followed was not swift demolition or renewal, but years of emptiness.

For more than a decade, the Fashion Plaza sat largely vacant—13 acres of silence in the very heart of Palm Springs. Too important to rush. Too complicated to easily redevelop. Too symbolic to get wrong.

Plans came and went. Economies shifted. The city debated what downtown should be.

The mall lingered—an absence you could see.

Desert Fashion Plaza demolition, c. 2014. Photo courtesy of The Desert Sun.

Demolition and redemption

In 2014, the wrecking balls finally arrived. Demolition felt less like destruction and more like closure.

Retail didn’t die downtown. It just had to breathe again.

The real lesson

Desert Fashion Plaza didn’t fail because Palm Springs lacked shoppers or style.

It failed because it misunderstood its setting.

Palm Springs thrives on:

wandering, not corridors

patios, not partitions

flirtation, not commitment

Retail moved to Palm Desert because it followed the preferences of residents, their need for convenience, and evolving shopping habits. Downtown Palm Springs survived by remembering what it always did best: being Palm Springs.

Major stores at The Desert Inn Fashion Plaza

The big anchors

I. Magnin — opened with the mall’s 1967 grand opening as a 20,000 sq ft anchor.

Saks Fifth Avenue — long-time luxury anchor and (per your earlier notes) the last major high-end retailer holding on into the endgame before leaving downtown.

Bank of America — listed among the mall’s “major establishments” from early on.

Joseph Magnin Co. — broke ground on a 26,000 sq ft department store at the mall in 1969 (designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill per the mall history summary) and later closed as the chain collapsed.

The connection between I. Magnin and Joseph Magnin

They’re related… and they were rivals.

I. Magnin was founded by Mary Ann and Isaac Magnin.

Joseph Magnin Co. was founded by Joseph Magnin, who was the fourth son of Isaac Magnin (i.e., same family), and his store became a competitor to I. Magnin.

So yes: Palm Springs had the very Palm Springs flex of hosting two competing luxury stores from the same family tree in the same mall ecosystem.

Other larger / notable tenants (named in early “major establishments” lists)

These are specifically called out as early “major establishments” that opened in the mall:

Belmont Savings & Loan

P’iddlers Three Restaurant

Stuard’s Sahara

Silverwoods (men’s clothing)

Islamania

Michael’s

Robert Sands Hairstyling

Master’s Candies

Village Card & Gift Shop

Orange Julius

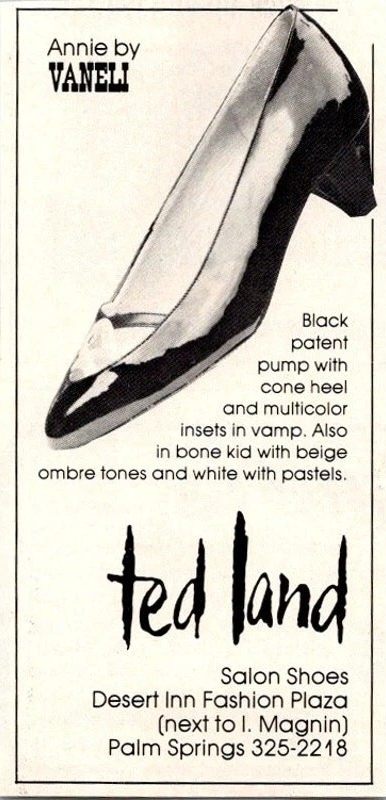

Ted Land Salon Shoes

Restaurants later (and yes, CPK in the 2000s)

Marie Callender’s — specifically cited as moving out during the mall’s decline (1991).

California Pizza Kitchen — yes, there was a CPK at 123 N. Palm Canyon at the Desert Fashion Plaza site; it’s mentioned as an operating tenant in 2012 and as closing “for now” in 2013 due to redevelopment.

Hamburger Hamlet — Yes, there was a Hamburger Hamlet at 123 N. Palm Canyon Drive, and the Palm Springs Historical Society catalogs a photo entry for it with that address.

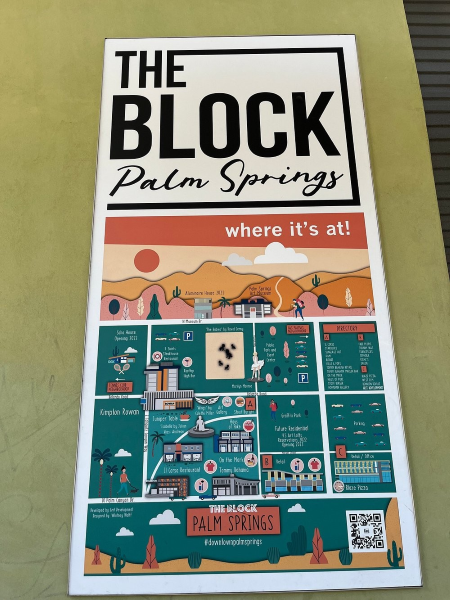

Flash forward to The Block

Flash forward to today: the site has been reborn as The Block, developed by Grit Development—a deliberate reversal of the mall experiment. Instead of an enclosed box, the redevelopment returned to street life and openness, a project that, fittingly for Palm Springs, arrived with both excitement and debate. From the start, The Block sparked controversy over height, massing, and how closely the buildings meet the street, a sharp contrast to the low-slung modernism many residents associate with the city’s past. But what’s hard to argue now is its impact: The Block has become the new heart of downtown Palm Springs, active day and night in a way the mall never managed. Anchored by the Kimpton Rowan Palm Springs, the development combines a boutique hotel, rooftop bar and pool, street-facing retail, restaurants, and public gathering spaces designed to put life back on the sidewalk. National brands like West Elm, Sephora, Johnny Was, H&M, Kiehl's and casual dining spots like Tommy Bahama Marlin Bar, Clandestino, Blaze Pizza, offering up a mix with pedestrian energy, events, and constant foot traffic. (The Block is also home to Bennion Deville Homes, our real estate brokerage for The Paul Kaplan Group.)

Unlike the inward-facing mall it replaced, The Block turns outward—embracing density, walkability, and visibility. Future plans continue to focus on activating downtown with hospitality, retail, and experiential uses, reinforcing a lesson Palm Springs learned the long way around: downtown doesn’t need to be enclosed to thrive—it needs to be lived in.

The fountain is gone.

The bells are silent.

And yet, this site remains the very center of downtown Palm Springs—layered with memory, reinvention, and more than a little controversy along the way. For those of us who lived here during the Fashion Plaza era, the mall isn’t remembered as a planning mistake or a missed opportunity. It’s remembered by sound: the echo of bells at the entrance, the rush of water inside, and the unmistakable feeling that this was where life briefly gathered.

We may laugh now at our fully air-conditioned devotion to retail, but once upon a time, those bells called us downtown—to shop, to linger, and to live our best, unapologetically material lives.

Lost Palm Springs, indeed.

Resources

- The Desert Sun

Wikipedia

“Desert Fashion Plaza” — Background on the site’s evolution from the Desert Inn through demolition, including ownership history, architects, developers, tenant anchors, and redevelopment timeline.Palm Springs Historical Society

Archival photographs, captions, and historical documentation of the Desert Inn, Desert Inn Fashion Plaza, bell tower entrance, interior fountain (Rainmaker), and tenant listings.The Desert Sun

Contemporary and archival reporting on the Fashion Plaza’s opening, renovations, decline, tenant departures (including Saks Fifth Avenue), vacancy period, and demolition.Alexander Construction Company (historical references)

Contextual background on George Alexander’s role in Palm Springs development and unrealized plans for the Desert Inn site.Home Savings and Loan Association

Ownership and development role in acquiring the Desert Inn property and commissioning the Fashion Plaza.Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Architectural attribution for the Joseph Magnin department store added to the plaza in 1969.Southern California Edison

Historical recognition of the Fashion Plaza’s all-electric design at the time of its opening.Grit Development

Information on the post-demolition redevelopment of the site as The Block.

Selling Your Home?

Get your home's value - our custom reports include accurate and up to date information.